“The Last of England” by Ford Madox Brown is not only a super-crisp, vivid image that perfectly captures the sensations of being in a small boat tossed about at sea, exposed to the wind, rain, and cold. It is a tragic self-portrait of the artist, his wife, and their baby, leaving England never to return, hoping to find better prospects in some distant land.

Update: You can now watch the video version I made of this article.

Before I launch into exploring the art, I want to give readers a chance to form their own impressions. On a purely visual level, there’s something that knocked my socks off when I first laid eyes on the painting. Is there anything that immediately impresses you? There is no correct response, but I’ll explain what that startling thing was for me shortly.

I also noticed something subtle and peculiar about this painting which nobody else has mentioned in any of the materials I researched for this article. Sometimes it takes an artist’s eye to catch things a historian, critic, or artificial intelligence will miss. Read till the end to find out what this strange thing is, if you don’t find it on your own. It is integral to the painting and fundamentally changes how it is understood.

Background

Ford Madox Brown painted “The Last of England” in 1855 when he was 34 years old. In 2023, that’s 168 years ago. And isn’t it great that Brown created an impression of a feared near future which never transpired, but which impacts us so freshly in the very present? Even though the artist died 130 years ago, his anticipation of the future is immortalized so that even now it gives the impression of the near future rather than the distant past.

It is an oil painting on panel in a round format known in art history circles as a “tondo”. The word “tondo” derives from the Italian rotondo, simply meaning round. Many Renaissance artists employed these circular compositions, and it’s a technique they borrowed from earlier Greek works. Brown re-adopted the same technique, partly in order to embrace and resuscitate the art and vision of the long past. Note that his painting is more oval than round.

In his focus on naturalistic detail, and luminous color, Brown’s work closely resembles that of his contemporary painters, the so-called “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”, though he was not officially a member. These artists, including his formal pupil, Donte Gabriel Rossetti, yearned for a return to what they saw as a less formulaic and artificial approach, as was practiced in Italy prior to Raphael.

Brown began this painting in 1852, during a period of mass migration from England, primarily to Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Canada. England’s promise of universal prosperity had dried up and its citizens sought to improve their prospects elsewhere, many never to return. Brown was struggling to attain professional success, and said of himself that he was “intensely miserable, very hard up and a little mad”. His contingency plan was to move to India.

Purely visual aspects of the painting

“Absolutely without regard to the art of any period or country, I have tried to render this scene as it would appear. The minuteness of detail which would be visible under such conditions of broad daylight I have thought necessary to imitate as bringing the pathos of the subject more home to the beholder.” ~ Ford Madox Brown

In Brown’s own words, his focus was on the minute, realistic details, which he believed would give his subject greater impact. We will delve into those impressive details, but there’s more to the painting than carefully observed realism, and it’s time to discuss the most impressive visual component of the image.

I don’t know what other people think it is, but for me it has to be the broad horizontal swatch of bright magenta that is Emma’s silk scarf slashing across the panel. It is the brightest and most saturated color in the painting, traverses the vertical center-line of the image, and connects the heads of the husband and wife.

One of the extraordinarily difficult challenges in making a representational image of this kind is recreating 3-dimensional illusionistic space in just 2 dimensions with physical mediums. There’s an alchemy to it by which inert pigment coalesces through human effort into an open window on a scene, and in this case, it’s a portal into the artist’s imaginary universe.

Brown sought not only to recreate natural phenomena but also to make a flat composition that is a very precise and geometrical arrangement of color, line, shape, and form. The magenta scarf is a striking assertion of the primacy of nearly abstract color and shape, precisely fitting like a puzzle piece into the 2D design. The effect of such audacious placement of color and shape is to highlight that the painting is both a naturalistic 3D image and a precise 2D design, simultaneously. This is true of many old master paintings, but few have made such a bold and conspicuous statement of it. It is, as I said, the first thing I noticed.

Brown wrote in his diary, “the ribbons of the bonnet took me 4 weeks to paint”, and he had once said in a parlor game that this brilliant shade of magenta was his favorite color. He certainly found the ideal excuse to share his love of the color.

color

Let’s look at a few more interesting color choices. If you said that the child’s sock was the visual focal point of the painting, I’d be impressed, as it is the only red in the painting, even if it is a much less striking color than the magenta. For me, it has a more significant meaning (more about that later).

There are two vivid triangles of purple. One is in the opening of her coat, revealing her clothes underneath, and the other is a cabbage hanging from the edge of the boat. You can follow the purple of the cabbage to the edges of the stack of books, up to the blood in the skin of the man’s knuckles, into the thumb of the woman’s glove, onto a button, and then to the woman’s chest.

Brown found a lot of excuses to use rust colors, which we would associate with the effect of sea water on iron, while no actual rust is depicted. It appears in the leather tarpaulin in the foreground, the highlights on the man’s coat, someone’s hair, another piece of fabric, a hat, and the inside of the dinghy.

Line

It’s not just the color, but every line, straight or curved, is meticulously arranged to complement every other, like musical notes in a string quartet. The edge of the husband’s sleeve forms a curved line that must be harmonious with the curve of the string connecting the hat to the button, with the right outer edge of the arm of his jacket, with the armature holding the dinghy, and with the long, delicate, white pipe.

The line of that pipe – its specific length, trajectory, and curvature – was as precisely strategized as a chess move by a grand master in a championship tournament.

You can find other significant lines yourself. Note that Impressionist paintings, for example, rarely have such presence of lines. They emphasize atmosphere much more. But in this art, line is essential and incredible.

Naturalistic Details

Brown was so dedicated to capturing the most subtle permutations of natural lighting and weather conditions that he endeavored to do the majority of the painting out of doors in his own garden. He was particularly pleased when the cold was sufficient to turn his hands blue, as he sought this effect in his painted image.

He asked his wife, Emma, to sit for him in all weather conditions, putting stress on their marriage. The blond girl eating the apple was modeled on their daughter, Cathy, and the baby in the mother’s arms is their son, Oliver.

There are too many textures to highlight them all: an array of fabrics, wood-grain, rope, vegetation, skin, hair, and waves among them.

I will just focus on the water droplets and the umbrella.

The painting contains a variety of types of water drops, each requiring a different technique for rendering. Is the drop on a dark or light surface, and is it reflecting the sun or not? What is its level of cohesion? Is it spherical, oblong, running, or dripping?

The umbrella is particularly complex, which is most evident in the contrast between the treatment of the inside and outside appearance of the fabric. On the inside, we can see the fabric is made up of horizontal striations, and the background light is shining through it.

The outside is more opaque, reflective, and covered with raindrops.

The striations are more fine and blurred, but the fabric is still semitransparent because you can see the brown of the wooden handle of the umbrella through it.

Notice that because of refraction, the handle seen through the fabric is not on the same trajectory as the exposed handle tucked into the man’s jacket. I think it’s safe to say this is the most intensely observed and rendered umbrella in art history.

Content of the Painting

Brown said that the painting portrayed “the parting scene in its fullest tragic development.” That was his objective, but what visual means did he use to achieve it.

First is his own intensely brooding stare, facing the future head-on, but with a mixture of fear, defiance, resentment, resignation to circumstances, and determination to survive. His overall countenance is that of an eagle.

Meanwhile, Emma is less visibly perturbed. Her face and view are shielded by the protective umbrella.

Their child, modeled on their baby son, Oliver, is almost entirely hidden. We can see the shape of his head bulging through his mother’s coat, and his hand clasped by his mom’s in the opening of the coat.

The father is touching the baby’s sock-clad foot, as if not only to reassure the child but also to remind himself that he is undertaking this adventure for his family. As I mentioned before, the sock is the only warm red in the painting, and is also arguably its heart, the place where the lives of each family member intersect.

We know there’s wind, rain, and the choppy, white-capped waves rock the boat. The passengers in the background seem huddled and holding on as if being tossed about.

The round format adds to the intimacy of the scene by giving the impression that we are looking at it through a telescope. This adds a voyeuristic element, so that the scene is more private than anything an observer is intended to see.

Brown saw the couple here as representing the disenfranchised middle class, as he put it, “high enough, through education and refinement, to appreciate all they are now giving up, and yet depressed enough in means to have to put up with the discomforts and humiliations incident to a vessel all one class“.

The title, “The Last of England” is a double-entendre, meaning that the family has seen England for the last time, and also that England is no longer the country it once was.

For the remainder of the painting, we can trust Browns own written description:

in the background, an honest family of the greengrocer kind, father (mother lost), eldest daughter and younger children, make the best of things with tobacco-pipe and apples, &c., &c. Still further back, a reprobate shakes his fist with curses at the land of his birth, as though that were answerable for his want of success; his old mother reproves him for his foul-mouthed profanity, while a boon companion, with flushed countenance, and got up in nautical togs for the voyage, signifies drunken approbation. The cabbages slung round the stern of the vessel indicate, to the practised eye, a lengthy voyage; but for this their introduction would be objectless. A cabin-boy, too used to “laving his native land” to see occasion for much sentiment in it, is selecting vegetables for the dinner out of a boatful.

The Mysterious Parts Nobody Addresses

So much emphasis is placed on the naturalism of the lighting and rendering of the details that everybody missed that Ford Madox Brown took great liberties with perspective and anatomy. You won’t find what follows in any description of the painting I’ve been able to find online.

Anatomy

Do you notice anything obviously strange about Emma’s face?

[Below] How about now?

In the first version, I’d adjusted the proportions in Photoshop to more closely resemble standard proportions. In the real painting, above, her mouth is much too small and no wider than her nose. The width of the average mouth extends to about the distance between the pupils.

Her mouth is tiny enough to fit in one of her eyes.

And her right eye has migrated up and off to the side because he likes wide-set eyes.

These aren’t mistakes. They reflect Brown’s personal and, to my tastes, somewhat peculiar aesthetic. You can see the same proportions in the sketch he made of Emma, in his painting “The Irish Girl” (1860), and in “The English Boy” [1860].

Of course Brown gave himself a similarly minute mouth, as well as the exaggeratedly large and stylized trapezoidal eyes.

If you compare a photo of Brown to his self-portrait in the painting, you can clearly see he doesn’t naturally have an undersized mouth or bulging eyes, but conventional human proportions.

As with Emma, his mouth is also small enough to fit in his eye, but not so in the case of the photo.

Again, I’m not saying there’s anything wrong here. Au contraire. It’s a question of what his style is, and these purposeful distortions introduce a level of romanticism and idealism into the painting that nobody I’ve encountered has mentioned. The art is more profound and beautiful because of them.

Perspective

The perspective in the painting is worthy of the Twilight Zone. It seems perfectly fine and accurate, until you study it closely. We see the back of the lifeboat straight on. The name of the boat is flat on the canvas, without any distortion of perspective.

Logically, because we see a substantial amount of the left side of the boat, and none of the right, the back should be tilted so that the text gets smaller as it recedes away from us to the right. This does not happen at all.

If you take the visible left backside of the boat and mirror it, you will see that, like the writing, it is flat to the picture plane. This was another deliberate device so that we could read “El Dorado”, an ironic name alluding to the myth of a kingdom of gold that several expeditions had sought to find.

From our vantage point, seeing the rear of the boat head-on, it would be impossible to see as much of the port side as we do, and the boat would have had to have been previously crushed against the cliffs of Dover for us to see the interior of the starboard side of the boat as well.

If that is not bizarre enough, once you’ve noticed it, if you plot the trajectory of the top edge of the side of the boat immediately behind Emma, several of the passengers in the background are not in the boat at all, but mysteriously floating along side of it.

The painting aligns itself with abstract and even subconscious laws of aesthetics spectacularly well, and these proportions take precedence over how physical reality actually appears. While there might be a few technical flaws that can’t easily be ignored, the painting is crafted according to the compass of the human eye and human emotions. It succeeds in this regard in a way that a meticulously hyper-realistic painting of a staged photograph would not. And while photography can do amazing things paintings can’t, this painting does something photography is incapable of. It simultaneously describes a scene in excruciating naturalistic detail while breaking the laws of physics in subordination to the laws of aesthetics and personal vision. In so doing, the painting bears the imprint of the artist’s inner vision. It is the blend of inner and outer reality, the subjective and the objective, in which both are convincing and compelling, that makes this such a powerful painting and portrait.

To end on an uplifting note, Ford Madox Brown is the grandfather of Ford Madox Ford, a famous novelist, poet, and critic. The little blond girl in the painting will become the writer’s mother. In the biography of his maternal grandfather, Ford Madox Ford wrote that the tragic painting in question was the first “to which anything approaching general praise was accorded”. This very painting, which envisioned the artist’s projected permanent estrangement from his home and abandoning everything he’d worked to build, was the very thing that saved him.

~ Ends

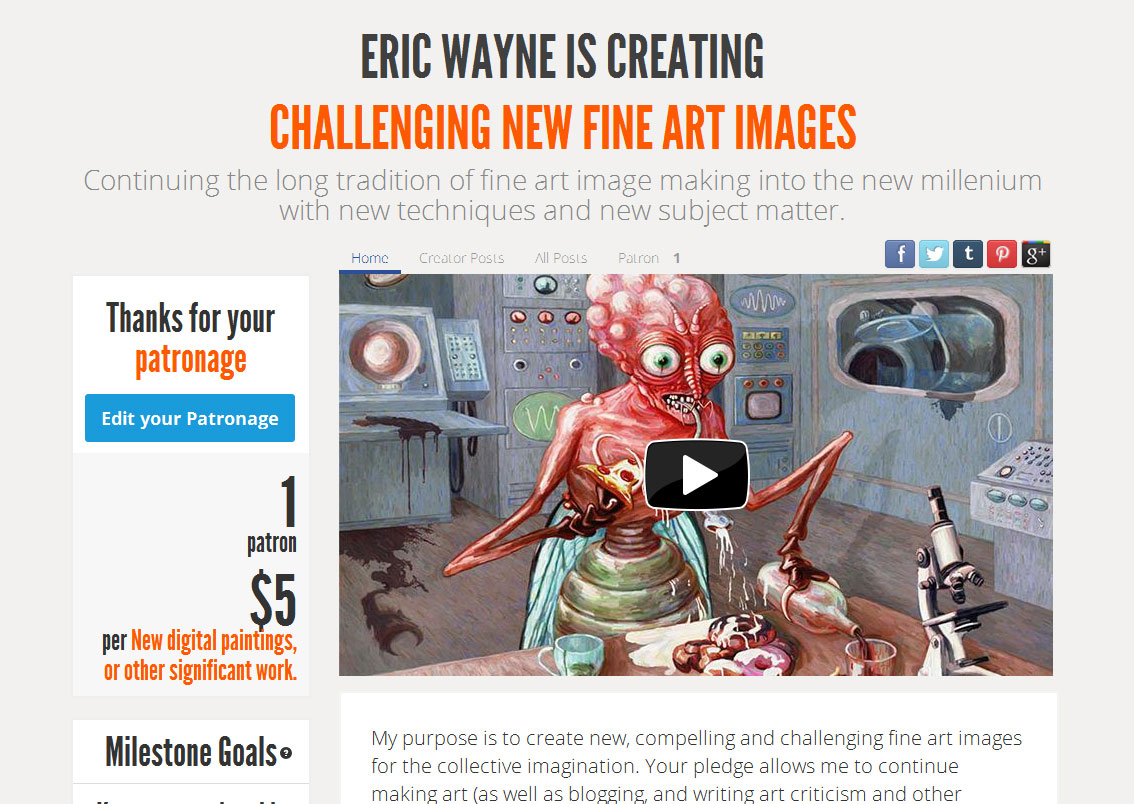

And if you like my art or criticism, please consider chipping in so I can keep working until I drop. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per month to help keep me going (y’know, so I don’t have to put art on the back-burner while I slog away at a full-time job). See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

❤️❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed this – thanks! 😎

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very cool! Before I read anything I looked at the image because a speedy peek made me think it was an AI piece or partly one. Yes, that amazing magenta scarf was the first thing to grab my eyes. The scarf did a lot of heavy lifting for me, straight into the rest of the image. Also, the scarf and bits of the passengers’ hair were the best clues (for me) that the boat/ship was moving, that there might be wind. Loved that! Yes, the tiny foot, the hands – all remarkable. But that background! Those guys in the back! Until I read your post I was nearly convinced that they – and the chaos in which they were trapped – were an AI image attached to the image of the painting. I thought you might be playing an AI prank! They figures are out-of-whack, one of the hands has what I guess is a foreshortened finger but looked like a typically mangled AI digit. Their [few] teeth, too, are oddly prominent and chunky. Maybe they were representative of the dental troubles some segments of the population suffered? The other people – heads, hands – are a jumble of confusion that I suppose gives contrast to the apparently still (except for hair & scarf) main figures. But, like I said, I initially thought people in the back were AI. 🤷🏻♀️ Oh! The tiny mouths! Haaa! Noticed them but assumed they were some kind of statement by the painter. Like a throwback to old paintings where facial components were strangely sized. Or that he was tipping his hat to the “pursed lips” expression people sometimes make when they’re under great stress and trying to force their way thru it. WOW…interesting image. And a fascinating post! Not proofing this, have to go. 🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right. The people in the back are peculiar. There are anomalies with the hands where people further away have bigger hands than people nearer. The little blond girl’s hand in the front is too small. It should be nearly the size of her face. I couldn’t cover everything.

There’s the natural size of things, how we perceive them, and then what works in a painting. Even the best painters made mistakes. It’s rare to NOT find one if I look hard enough, unless they are working very closely from photographs, some sort of projection, or otherwise copying an example very closely.

Funny you thought AI was involved. AI has gotten so much better in the last months that in the future if you see mistakes it might tip you off that a human made it, rather than AI. I’ve already shifted to valuing human small error as a badge of authenticity, and that the work in question reflects the natural limitations of a human being. Nobody is perfect. We are all at least slightly imperfect at our very best, and our imperfections are like our fingerprints, especially as artists when we make our own work (if it isn’t copying).

This painting is such a mash-up of pieces collaged together that it’s a small miracle he pulled it together at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

OK – I looked up Brown, saw ref to his “Work.” Yeeeeeeooow. LOVE that painting! The details, the many stories possible in it! Thnx for the inspiration to check him out. 😄

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, right. “Work” was hugely ambitious. It’s like a sprawling novel with lots of characters. I haven’t even tried to process that one. So much going on. He is a very interesting artist. For me, “Last of England” is his masterpiece, but I may be in the minority on that opinion. Glad you were inspired to look him up. I gather he’s more popular in England than the states.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fantastic analysis of this painting, thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, glad you liked it. I’m planning a video, and once I wrote the narration I thought, “Why not just make this in to a blog post by adding pics”. Your approval is encouraging. Maybe people will like the video.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I certainly will! I loved your video about the Salvator Mundi painting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In an age of Tik Tok, YT shorts, and scrolling, it’s refreshing to have you take us on a tour of such a magnificent painting in all its details! Thank you. Looking forward to your video, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderful tour of a well known painting. I know it, and like it, but after your tour I certainly appreciate it better.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, man. I never saw it through a masters in art. More of a British thing, I guess. The text is borrowed from my narration for a video I’m making, so, the video should be better because the imagery will be more seamless, etc. Thanks for reading and commenting!

LikeLiked by 1 person